When looking at our childhoods we can often miss pivotal clues as to how emotional neglect can contribute to later difficulties in adult life. As a society we often focus on abuse in terms of what was done to us as children and yet what actions our parents may have failed to take can be just as damaging. If parents failed to act to meet our emotional needs, reflected things back to us so that we had a mirror to understand our feelings, emotions and needs and reflect back positive parts of self, then growing up it is likely that we become adults unable to express ourselves or be in tuned with our feelings. This can leave us unable to recognise our needs or emotions, have problems knowing what we need and how to express ourselves. We may have difficulties calming ourselves down and soothing ourselves from painful emotions which can lead us to escape them through compulsive behaviours. We might have difficulties with emotional regulation, expression and ways to articulate our feelings. We may even have difficulties asking for what we need.

Developing a positive sense of self becomes challenging as children. Our sense of identity and self tends to get lost if emotional neglect has taken place in our childhood, and this leads to feelings of emptiness, feeling disconnected, unfulfilled and not being able to know why. As adults, we may then not be able to trust our own emotions. Individuals who have experienced this may therefore have problems taking care of themselves and knowing how to nurture themselves and their wounded inner child. They can remain unaware of the impact of what has happened to them and in the process neglect themselves.

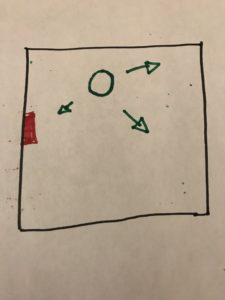

Emotional neglect renders the person invisible, it’s a failure to notice, attend to or respond appropriately to a child’s feelings. It remains invisible as it goes unrecognised and so the child’s experience feels invalidated. It remains an overlooked issue and children themselves remain unaware until symptoms manifest in early adulthood. Even then confusion is to be found due to the fact this is an invisible scar and hidden pain.

There are a few parenting styles that can result in emotional neglect:

- Absent parents – Reasons could be due to family break ups such as divorce or separation, a parent absent due to illness or addiction or mental health, a parent that may be serving time in jail, a deceased parent or a parent that has left the home and family.

Some situations are not the result of bad parenting, however the impact remains:

- Authoritarian parents – those who cut off and silence a child and by this silencing their feelings and needs

- Permissive parents – who leave the child to fend for themselves, so that the child is never shown how to recognise their own feelings by never having them recognised

- Narcissistic parents – where the child is used to cater the needs of the parent alone, never being able to have their own and theirs met

- Perfectionist parents – who project their own need for perfection on a child and the child never feels good enough.

All these behaviours ignore a child’s needs and feelings and require the child to sacrifice their own needs and feelings to accommodate others.

Like everything in life, the things that are not visible to us tend to get ignored, yet they are just as damaging and the damage is being done. Let’s take the example of drugs, alcohol, refined sugars and tobacco. These damage our bodies – we cannot see the damage that goes on within our bodies but these toxic substances are doing just that. After much abuse, we see symptoms and start to notice the effects; this is much like the invisibility of emotional neglect and the fact that just because it cannot be seen doesn’t mean the damage hasn’t or isn’t occurring.

Psychologist, Dr. Jonice Webb states: “Childhood emotional neglect is often subtle, invisible and unmemorable”. Emotional neglect can be at the root of emotional disorders and mental illness such as depression and anxiety. Its symptoms include:

- Sensitivity to feelings of rejection

- Pervasive feelings of emptiness

- Sense of not feeling fulfilled

- Unhappiness

- Perfectionism

- Need to people please

- Feeling like a fraud

- Disconnection from self

- Excessive fears and worries

- Dissatisfaction

- Difficulty identifying or expressing feelings

- Being seen as aloof, arrogant or distant.

Children may develop ‘toxic stress response’ and this makes the process of growing up an extremely challenging one. Parents who have experienced emotional neglect themselves may emotionally neglect their own children, not knowing any better as not having experienced any other way of being themselves.

Emotional neglect however is not limited to childhood and is just as damaging in adult life. This can happen within intimate relationships; it feels like rejection and rejection can be painful. In fact feelings of rejection and abandonment are said to send a signal to the part of our brains known as the amygdala, which the triggers intense fear. This is the fear that we are not good enough, unacceptable or unlovable. We then can no longer feel safe and secure.

To heal these wounds as counsellors, we need to not only be aware of what has happened in our clients childhood but what has been missing in it and the gaps created. We need to offer our client’s unconditional positive regard so that they can learn to nurture themselves, through self love and self compassion, and connect to their self so that they become aware of their own needs and feelings and how to nourish these. Clients need to find their own empathy to reconnect to the self, for empathy drives connection and through our empathy to clients this can help drive that connection. Many inner conflicts and addictions or mental health problems, or emotional disorders can be the result of being disconnection from ourselves and life.

As professionals we need to help spread light into the hidden corners that often go unnoticed.

https://www.counselling-directory.org.uk/memberarticles/invisible-scars-emotional-neglect

Shattering the myths of abuse: Validating the pain; Changing the culture –

Shattering the myths of abuse: Validating the pain; Changing the culture –